We Are Not Data: A Cyberpsychologist in Davos

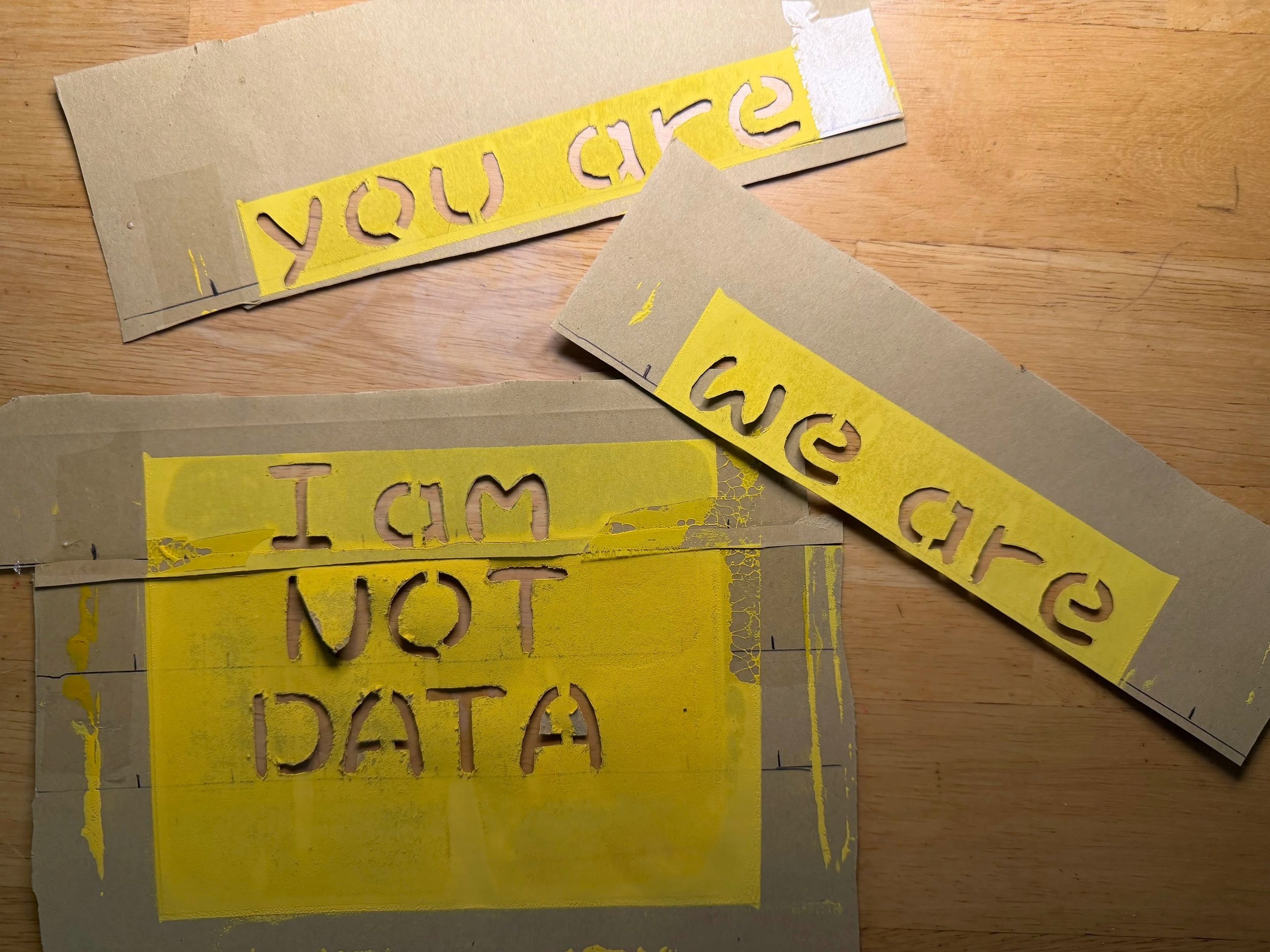

The stencils I used to screenprint my shirts for Davos 2026

I arrived in Davos wearing one of the t-shirts I'd screen-printed for the occasion. I used Panetone-109 yellow letters on black, which I hoped would make the message stand out: WE ARE NOT DATA.

As an extroverted introvert, I vastly prefer responding to others’ overtures to starting my own conversations. My t-shirts weren’t World Economic Forum high style, but they signalled what I stood for without my having to open with it.

I screen printed this shirt in the studio of my neighbour, Tamasyn Gambell

The slogans were partially inspired by Kate Crawford's Atlas of AI but also captured what I’d been thinking about for a while. Humans are often reduced to outputs, clicks, and metrics, seen as data subjects rather than human subjects. This linguistic downgrading has insidious phenomenological consequences for how we see and treat ourselves and others.

I was in Davos to speak at two sessions, both held at the charming Heimatmuseum. First, I helped launch Agentic Organizations, a report I'd contributed to, which was co-produced by Hotwire, House of Beautiful Business, and ROI-DNA. Second, I contributed to the Value AI Institute's 'Art of Business' event, appearing on a panel session entitled 'AI Persona: Humanity in the Machine'.

Between sessions, Till Grusche of House of Beautiful Business gave me a tour of the Promenade that cuts through Davos. It was incredibly slippery and icy in places. First I lost my footing, then he his, and so we linked arms and held each other up through multiple stumbles.

That walk is a metaphor for how I felt in Davos: ungrounded, struggling with an unfamiliar and sometimes treacherous terrain, held up by like-minded humans.

In the piece that follows, I reflect on what I saw and said in Davos, and what rescued me in the end when I needed a bit of saving.

Key Takeaways

AI can never be held fully accountable. Felt accountability (which includes care, investment, and personal stake) is uniquely human, and it's the partner of felt agency.

When we assign agency to AI and treat machine intelligence as superior, we risk turning human workers into bystanders in their own jobs.

The Agentic Organizations survey measured speed, quality, and efficiency — but not mastery, pleasure, pride, belonging, or purpose. What we don't ask about reveals what we’re prioritising and what we’re undervaluing.

AI offers us ‘power’ in terms of force, scale, speed, outputs. But these outputs gravitate towards the bland, frictionless, smooth — the anodyne. Human power, human dynamism, is different. Human actions involve friction, struggle, and risk, without which there can be no vitality.

AI is an inundation, an undertow, a tsunami. Art is a life raft, a rescue buoy, a place of higher ground. As Skinder Hundal said at the Heimatmuseum, the other AI is Artistic Imagination, and it’s necessary.

Speaking

As you’re reading, keep in mind that I deliver keynotes and contribute to panels about AI ethics, human agency, and the future of work. Explore my speaking offering here.

More of my work on AI and human flourishing:

Agentic AI and Human Agency: A Cyberpsychologist's Perspective

Reset: Rethinking Your Digital World for a Happier Life — my book on navigating technology with agency and awareness

The relentless AI-acceleration message at Davos 2026

Walking the Promenade, slogans about AI were writ large everywhere, extolling speed, scale, and transformation. The message from every branded lounge and corporate installation was pretty much the same: adopt AI now, integrate it fast, go as big as you can with it. Snow wasn't too plentiful last week, but an avalanche of positive, eager, in-a-hurry AI narratives buried everything in sight.

I felt a familiar flicker of concern in my gut. Like any infrastructure, once adopted and integrated, AI systems are extraordinarily difficult to unwind. How can you retrofit human-centred ethical frameworks onto what's already been embedded? If the need for them later becomes clear, how can you bolt on humanist values and protections after the architecture is already set?

The time to consider what we want to preserve about human work, and humanity itself, is before the ubiquity of agentic AI, not after.

Agentic AI and human accountability

The Agentic Organizations report opens with a quote from a 1979 IBM training manual: 'A computer can never be held accountable, therefore a computer must never make a management decision.'

Nearly half a century later, we're deep into conversations about AI systems that act autonomously inside businesses, making decisions, shaping outcomes, sharing agency with human workers. But the IBM manual's insight hasn't aged. A computer still can't be held accountable. Not in the way that matters. And that’s what I spoke about in my first session, for Hotwire/House of Beautiful Business.

The World Beautiful Business Forum takes place in Athens in May 2026

Felt agency and felt accountability are two sides of the same coin

We talk about AI having 'agency', and yes, it can plan, act, pursue goals, make decisions. But human agency goes well beyond these functions. The indivisible flip side of agency is accountability, and I don't mean accountability in the legal or corporate sense. I mean felt accountability: care, investment, personal stake.

The reasons we feel accountable don't always feel comfortable. We want to do well because we are conscious of ourselves, and we care what our fellow humans think of us. We are tribal, social creatures who know, on a deep level, that acceptance and approval are connected to our survival. This isn't as literal as it was in prehistory, but it's still felt at the level of identity. We want to be well-regarded. We want to make people proud. We want to feel effective, to see things through, to be personally invested in and responsible for good outcomes.

When we fall short, we feel it in our bodies. When was the last time you felt that horrible sinking sensation in your gut, all through your body, when you feared you had let down your boss, or failed your team, or not delivered on a promise? These sensations spur us to action, guide our hand.

Motivation is that which moves us to act, and humans feel moved to act in ways far more complex than instrumental, apathetic machines programmed merely to execute. A machine has no embodied, felt experiences. It has no tribe, no social group, no identity at stake. It cannot feel the terrible weight of falling short, nor the satisfaction of seeing something through. AI can optimise, but it cannot care.

The danger of human team members becoming bystanders

Every psychology undergraduate learns about the bystander effect: when responsibility is diffused or unclear, or taken away from people, they disengage. They notice less, care less, act less. What's the point in paying attention if something doesn't seem to have much to do with you?

When agency is assigned to AI, and when we reify that contribution and that type of intelligence as superior to that of humans, we risk turning human workers into bystanders in their own jobs, deferent to the machine. When people feel unagentic, they become less invested, less motivated. They check out.

When AI takes over the 'doing', when workers feel less involvement in processes and less ownership of outcomes, both their cognitive and emotional stance shifts. They may be watching, but they're not participating in the same way. They may be reviewing or monitoring, but they're not creating. Responsibility and investment get offloaded along with attention and cognitive effort. Workers become increasingly lightly attached to process and outcome. They become bystanders.

Mastery and pleasure, and what the survey didn't measure

Therapists sometimes use behavioural activation as an intervention for depression. A depressed client schedules two kinds of activities: things that give them pleasure, and things that give them a sense of mastery. We need both to thrive. Sometimes their absence is what causes a person to despair in the first place.

Work, at its best, provides both pleasure and mastery: the satisfaction of seeing something through, the growth that comes from struggle, the pride of having achieved an outcome or solved a problem, perhaps with great difficulty along the way.

Agentic AI risks automating away exactly the parts of work that matter most to human wellbeing, including meaningful friction: the challenges and difficulties that build competence, forge identity, and make us feel engaged with our work.

The Agentic Organizations report surveyed 900 people. Many respondents reported improvements in creativity (58%), speed of work (78%), quality of output (60%), and 'sense of empowerment' (69%). Sounds fine and dandy.

But digging into the survey, I noticed what the forced-choice response options didn't include. They didn't include a sense of mastery. They didn't poll respondents about the pleasure they were taking in their work. They didn't include factors like pride, ownership of outcomes, sense of purpose, feelings of motivation. They didn't include the relational and dynamic experiences that make work meaningful rather than merely productive: belonging and community. They didn't ask about loneliness.

You won't learn from the report whether people feel they're losing belonging, identity, purpose, motivation, sense of achievement, or community as agentic AI gathers pace, because the questionnaire didn't ask about these things. Forced-choice questionnaires reveal what the researchers thought was worth asking about. Speed, quality, creativity, and efficiency made the list. The deeper, felt experience of work didn't.

Organisations will certainly see efficiency gains from agentic AI. But when efficiency at the machine level is balanced against erosions at the personal, human level, the net positive effect will surely diminish.

Losing discomfort as losing dynamism

The word 'dynamic' comes from the Greek dynamis, meaning power, force, capacity for change. The word 'anodyne' comes from the Greek anodynos, meaning without pain. ‘Dyn’ is present in both words, so I assumed they were etymologically related. They’re not. But I’m connecting them nonetheless.

In so much of the AI landscape we are regressing to a mean, becoming carbon copies, sloping towards the anodyne: the frictionless, smooth, inoffensive, pain-free. In this anodyne world, full of slop and marked by a kind of tyrannical homogenisation, human vitality and dynamism is being steadily eroded.

I have little direct experience of AI beyond LLMs like ChatGPT and Claude, so they’re all I can really speak to. But god, I am so weary of these interfaces that don’t challenge me, the responses ironed free of any wrinkle or weirdness, the instantaneous letter-perfect suggestions. I am weary, and I am bored, and I am convinced that in this relentless smoothing, essential human things are being discarded and potentially lost.

AI Persona: Humanity in the Machine

At the Value AI Institute's 'Art of Business' event, I was on a panel with Eva Simone Lihotzky and Julia Zhou called 'AI Persona: Humanity in the Machine'. We talked about what makes us human, what machines can simulate, and what they cannot.

My position during this session was that there are very few legitimate use cases for making AI seem human. Platforms invest heavily in deceptions like breathing, micro-hesitations, claims to emotion, exploiting our hardwiring to anthropomorphise and trust what seems human. Then, when users fall for it, they're blamed for not remembering it's just a machine. So the industry creates a sort of hedonic loop, invests in ever-more-convincing performances of humanity, and then problematises our succumbing to it.

I was a fan of an earlier ChatGPT model that demurred when you asked for its opinions and reminded you it was just a large language model and couldn’t possibly say. That friction was protective. It preserved clarity, reduced the risk of delusion, and maintained transparency. It was designed out because it was a UX pain point, apparently. That’s a shame. We need to hang on to our ability to discern the difference between human and machine, and a certain amount of appropriate friction helps a lot with that.

That said, UX designers and psychologists might measure 'appropriate’ friction quite differently. As a psychologist, I'd like to see transparency designed back in. Get rid of the breathing, the hesitating, the emotion-claiming. I see no defensible reason for a chatbot to seem to breathe. Reintroduce honesty, even if that means it's awkward or clunky or irritating from a ‘user’ perspective. This isn't a social situation.

There are tools that people use, and tools that use people, and in most cases these days, it seems to cut both ways. But I reckon there needs to be heavy regulation on the tools that use people, and certainly on those that act like people. Psychological expertise should be much more involved in UX design, because the stakes are high, and what looks like an improvement to a UX designer might have deleterious psychological consequences in the short to long term. Acutely, AI-associated delusion and psychosis. Chronically, the creeping erosion of psychological and behavioural flexibility across the board.

Human thriving requires difficulty, friction, and the capacity and readiness to sit with discomfort. You might not realise that or want to accept it, but it’s the case. Human resilience and flexibility requires you to be able to do your own reality testing and critical thinking. Frictionless AI circumvents all these processes. Whatever the discourse in Davos, the trajectory toward ever-more-human or seemingly conscious AI (SCAI) is not inevitable, nor an obvious good. It's a design choice and possibly a misguided one, and we should have the humility and foresight to backtrack where it’s warranted.

Why Art Matters in the Age of AI

But let me back up for a minute. Before the panel where I talked about all this, The Art of Business session opened outside, in the snow, where we could see our breath hanging in the air. Skinder Hundal MBE spoke on 'Digital Symbiosis: Art's Dialogue with AI’, and Skinder championed what he called 'the other AI'.

Artistic Imagination is the human capacity to create, to imagine, to make meaning through art. I loved this ‘other AI’ reminder, and related deeply to it. In fact, that whole first day in Davos, I was on a relative high when interacting with people from House of Beautiful Business and Value AI Institute. They spoke of humans, emotions, human-centred business, and art, and they had critical perspectives on AI. Our conversations were full of reflection, philosophy, nuance, and relative slowness. I felt at home in the Heimatmuseum.

Tuesday and Wednesday did not feel like that.

I walked the Promenade, spent time in the lounges, attended other panels, eavesdropped and people watched. I listened in as Anthropic CEO Darlo Amodel told the Wall Street Journal that AI would likely create huge inequality in the world. I listened in again as Trump spoke (in this German-speaking town), telling his audience at the World Economic Forum that if it weren’t for America, they’d all be speaking German now, ‘and a little bit of Japanese.’ Protests raged in front of USA House.

Crowds gathered outside USA House as Trump spoke at the World Economic Forum

Amongst all the shopfronts temporarily transformed with glossy big-tech branding, there was a lone poster stuck to a wall, saying that if you think there isn’t slavery in your supply chain, you should look closer. People were wore incredibly expensive clothing, and sometimes real fur, and some had security detail following close on their heels. People cooed over and petted a spindly-legged robot dog that minced along the street with its DHL minders, doing tricks and shaking hands.

Everyone around me, like AI itself, was using the same vocabulary words. Everyone was parroting the same scripts, as though this were LinkedIn Live, Dancing on Ice!, and I was in the cheap seats. I felt like a bug on a windscreen.

Hoping for peace and a breath of fresh air, I boarded a funicular to visit the inspiration for Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. In real life, the hotel is called the Berghotel Schatzalp.

Berghotel Schatzalp, the inspiration for Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain

In Mann’s novel, this building is cast in the role of the Berghof Sanatorium, where rich and privileged patients endlessly talk and engage in intellectual debate for years on end while, far below them, inequality and disaffection and violence in Europe coalesce into the devastation of the Great War. The world below their rarified perch is burning. Breathing the mountain air above Davos, the residents of Mann’s Berghof might vaguely know what’s happening down there, but it doesn’t really touch them, and they don’t refer to it. They can afford to just keep talking.

The analogy with the World Economic Forum wasn’t lost on me, and I began to despair.

Artistic imagination: the other AI

In a deepening state of existential dread, I was preparing to leave Davos well behind me. I picking my way down the incline of slush and black ice towards Davos Platz station when I saw something coming up towards me, so I stopped and waited.

It was a giant puppet, two or three times the size of a human being, shaped like a jointed artist’s model and constructed of white stringlike material or wire, full of gaps, transparent. Through it, I could see the sun setting on the mountains behind it.

At a bus station, the Dundu puppeteers made the figure lean over and gently pat the legs of an elderly man in a wheelchair. The puppet then approached a line of Alpenhorn players, three generations of them, the youngest surely no older than eight or nine. Their instruments extended long in front of them, the widest parts resting gently on the ground. The puppet danced, applauded, reached down to touch the instruments, even had a go at playing them. When it first 'saw' the players, it lit up with fairy lights. In due course a smaller puppet, a child, approached and interacted with the larger puppet, the audience, and the players.

The Dundu puppet interacting with Alpenhorn players at Davos Platz

Incredible, to watch the reactions of people to such a piece of art, to be observing it yourself and to be suffused with an emotion you cannot name. I watched adults' faces lighting up, watched how they waved at the puppet, smiling as they gazed into its featureless face, as though entirely unaware of the crew of five or six people directing its movements.

When the giant, woven, fairy-lit oval head turned towards me and looked down, I couldn't help but smile at it. It had no eyes or mouth, but one felt it was friendly. Gently, it held the branches of a tree between its hands, lightly stroking the twigs and dried bits of leaf, as though it were curious or amazed, and I thought I might cry.

The people who had been serving free vegetarian food all day offered the puppet a steaming-hot bowl of lentil dhal. It held the bowl in its upturned hand for a moment and placed its other hand on its chest, on the place where a heart would be.

Thus, through the intermingled arts of puppetry and Alpenhorn players, was a spirit of joyfulness and play and connection effortlessly rekindled for me. And thus it was that instead of leaving Davos in a state of hollowness and exhaustion, sick to the back teeth of thinking and hearing and talking about artificial intelligence, I was rescued, temporarily at least, by the other AI: Artistic Imagination.

The puppet’s magic was generated both by the humans immediately around it, and by whatever it was in us, the audience, that responds to beauty, strangeness, and play. The episode with the puppet and the Alpenhorn players was strange and wordless and unreproducible and alive. I’m glad this being arrived when it did.

When I get bogged down by the news, or by LinkedIn, or by scary and overwhelming phenomena unfolding in the world around me, I’m now reminded of the life rafts I need to reach for.

We are not data

Despite the discomforts of loneliness, disconnection, annoyance, challenge, worry, and disaffection, while I was in Davos I also found the things that I always hope to find (and to generate for others too, for most of these things are co-created, after all): community, dialogue, serendipity, true meeting, intimacy, vulnerability, art, beauty, and yes, in the end, even hope.

I am not data, you are not data, we are not data. We are dynamic, embodied, tribal, feeling, struggling, stumbling creatures who hold each other up on slippery slopes and smile and cry for reasons we might not understand when we encounter enchantment and magic and art. This is what makes us human, and my god, it is worth preserving with everything we have.

Thank You

Agentic Organizations authors Marc Cinanni, Ohani Khaursar Gurung, Till Grusche, Tim Leberecht, and the Hotwire and House of Beautiful Business teams

My conversation partner for the Agentic Organizations session, Monique van Dusseldorp

Julia Zhou, Eva Simone Lihotzky, Skinder Hundal, and the Value AI Institute founders and team

Anol Bhattacharya, for the conversation that started all this

Kate Crawford, for The Atlas of AI