AI Therapy and the WEIRD Men Who Want to Fix You

Credit to Valeria Nikitina on Unsplash

In 2005, I gained my clinical psychology doctorate in the state of Illinois. Twenty years later, in August 2025, that state signed the Wellness and Oversight for Psychological Resources Act (HB 1806) into law, effectively prohibiting autonomously conducted AI therapy and severely limiting AI’s uses by licensed psychological professionals.

Then, earlier this week (November 2025), a colleague sent me a LinkedIn post from Reid Hoffman, the co-founder of that site, the world’s largest professional networking platform. The interviewer had just asked his opinion about Illinois’ near-ban on AI therapy. In the video attached to the post, Hoffman passionately responded, gesticulating and waving his arms to drive home his points as he compared the standards for AI therapy to the standards for autonomous vehicles (AVs).

‘When deploying AI for critical human use cases (e.g. Therapy),’ he wrote [emphasis added], ‘our goal should be “better than an average therapist,” not “a therapist that makes no mistakes”. The same principle applies to autonomous vehicles. The benchmark is not zero accidents; it’s a system that is safer than a car driven by a human.’

As Hoffman spoke, the video showed graphics of driverless cars in action.

‘If we wait for 100% safety before OK'ing new technologies,’ Hoffman’s went on to say, ‘we end up withholding enormous benefits from the very people they're meant to help' [emphasis added, again].

As I read and listened, I was hit once more by a thought that’s been nagging me, and I need to talk about it now. I can’t promise it will be maximally coherent. But that’s okay.

Clients and therapists are talking about and trying AI therapy. Tech companies push AI therapy. Journalists and pundits report and opine on AI therapy. But forget about the ‘AI’ part for a minute.

What are we assuming that therapy is? What do we think therapy is for? What do we believe a therapist should be?

And importantly: why are we thinking about therapy and therapists that way?

The WEIRD Founders of Yesterday’s Psychology and Today’s Technology

An early 20th century Viennese man invented psychoanalysis: Sigmund Freud. From that point, with a handful of notable exceptions, the development of psychological theory and therapeutic practice throughout the 20th century was dominated by one demographic: white men from Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic countries. Psychotherapy’s founding and trajectory is indisputably WEIRD, and perhaps there is something of the male-founder archetype in this history.

(Why am I saying perhaps? As a woman, I’ve been conditioned to qualify some of my observations as though I’m unsure, even when I’m not. So I’ll say it more plainly.)

The WEIRD history of psychology and psychotherapy is paralleled in the WEIRD history of the technology platforms that now rule our lives, and the WEIRDness of both are now compounding each other.

Let’s start with psychology.

Spot the similarities in the most influential psychologists of all time, according to Google.

The guru-esque mysticism of Carl Jung, a wealthy middle-class Swiss.

The Gestalt theory of the charismatic, manipulative, exploitative Fritz Perls, white middle class.

The control-focused, judgmental, aggressive Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT) of Albert Ellis, proponent of the 'snap out of it' philosophy satirised by Bob Newhart in his 'Stop it!' sketch. He was born lower middle class, but went on to be educated at Columbia University.

Cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) founder Aaron Beck, more Socratic than overtly confrontational but still disputational. Beck applied a WEIRD lens in deciding what types of thinking were faulty or distorted, which rational or logical. He came from a middle-class family and attended the elite institutions Brown and Yale.

BF Skinner, a middle-class white American who did his PhD at Harvard. His behaviourist theories are the basis of BJ Fogg’s Stanford Persuasive Technology Lab, where the movers and shakers of Silicon Valley were taught how to shape people’s behaviour.

I could go on: Freud, Erikson, Maslow, Rogers, May, Yalom. Their theories and approaches vary. Their WEIRDness does not.

By the way, why is the acronym so apt? Only about 12% of the world is WEIRD. In other words: the people who determine the norms are not normal.

I hasten to emphasise: within that group, there are plenty of good, prosocial, reflective people who are committed to questioning and changing things that are harmful in the world. In order to do that, however, there is much historical baggage that they must become aware of and work to shed.

Now, the people determining the norms are the founders of the America-centric technologies on which the world depends: Google, LinkedIn, Meta, X, Microsoft, OpenAI.

Spot the similarities, take two. Most famous tech founders, according to Google.

Bill Gates of Microsoft. White American, upper middle class, hailing from Seattle. Dropped out of Harvard, but originated from privilege, and surely it was a privilege-driven decision to drop out.

Mark Zuckerberg of Meta. White American from an upper-middle-class family in the New York suburbs, another Harvard dropout. (The ability to attend someplace like Harvard and then choose to drop out is seemingly as much a status marker as graduating.)

Larry Page and Sergey Brin of Google, both white Americans from upper-middle-class academic families, both Stanford doctoral students.

Jeff Bezos of Amazon, another White American with a middle-class background and a Princeton pedigree.

Elon Musk of Tesla, SpaceX, and X/Twitter, a wealthy White South African who moved to Canada and the US, graduating from Penn.

Peter Thiel, co-founder of PayPal, a White German-American from the upper middle class who attended Stanford Law.

Sam Altman of Open AI, White American from an upper-middle-class professional family, a Stanford dropout.

Where are the women?

In 20th century psychology, a few names stand out as influential. The daughter of Sigmund, Anna Freud. Melanie Klein. Karen Horney. Helene Deutsch. Margaret Mahler. Elizabeth Loftus.

In tech founder circles, I can think of Whitney Wolfe Herd of Bumble, Martha Lane Fox of lastminute.com, Melanie Perkins of Canva, and a handful more.

When it comes to the giddy heights of power and influence in psychology and technology respectively, though, these women’s names are not on the tips of our tongues and hold less of the immediate recognition factor of the more numerous and powerful males in these spaces.

The ratio of male to female 'founders' of important, influential theories of psychology is similar to the male-to-female ratio for tech founders, I reckon. These ratios are stark, depressing, and consequential.

So the men who have historically dominated both our tech environment and our psychological environment, who continue to pull the strings from beyond the grave and within Silicon Valley, shape what and how we think. The Internet perpetuates dominant 20th century theories about how humans tick. Both psychology and the technological landscape are algorithmically skewed in favour of assumptions that serve the WEIRD, and they are now mutually reinforcing one another.

Without realising it, as we debate AI therapy, we are engaging in unreflected assumptions about what therapy is. Those assumptions themselves threaten and diminish the therapeutic profession.

WEIRD Assumptions About How Therapy Works

I could write a laundry list of the assumptions that dominate WEIRD thinking about mental health and psychological pathology, but here I offer a starter list. Of course, it doesn’t represent everyone, but it does describe, I think, an unconscious undertow that will pull us along if we let it.

The WEIRD like to think that we can control minds, thoughts, feelings (and thus ultimately our fates), and that if we cannot, we are weak. If we only try hard enough, if we can only build the skills, we can wield this control using rationality and logic.

The WEIRD often regard psychologists, coaches, and other experts as gurus or teachers who can lead one to optimisation, or at least support continuous self-improvement, both of which are deemed desirable. Therapists are providers (insurance companies call them that) selling self-improvement tools to their customers. The analysts have been analysed and are now Subject Matter Experts, their therapy clients’ minds being the Subjects. The therapeutic provider is in an elite category, equipped through their deep knowledge and skills to help the still-broken out of their suffering, or the not-yet-perfect into perfection. They are credited with knowing you better than you know yourself.

For the WEIRD, the essence of therapy lies in words. How well can you articulate your experience? How incisively and accurately can it be articulated back at you? How well can you understand, explain, communicate? Your ability to do these things in dialogue with another person, as though you were star pupil in a seminar about yourself at Harvard or Oxford, is what determines how successful your therapy will be. Forget about embodiment, community, communion, ritual, the art of therapy. These things are for illogical people who don’t appreciate science.

The WEIRD believe the problem lies within you, and therefore you should bring it under control. It’s not the system, it’s nothing to do with politics, or economics, or society. It’s not the relationships in which you’re embedded. Those are excuses. (Sometimes, a new client comes in for individual therapy for what’s clearly a couples problem; an issue with a terrible boss; a terrifically toxic work environment. I ask about these things, and they demur, saying, 'I need to fix myself first.')

The WEIRD feel comfortable with emotional disclosure to a stranger because a therapist is thought to be ‘objective’ and ‘neutral’; their training and professionalism has supposedly trained bias out of them. It isn’t how connected a therapist is with you that makes the real difference in therapy, it’s how disconnected they can be.

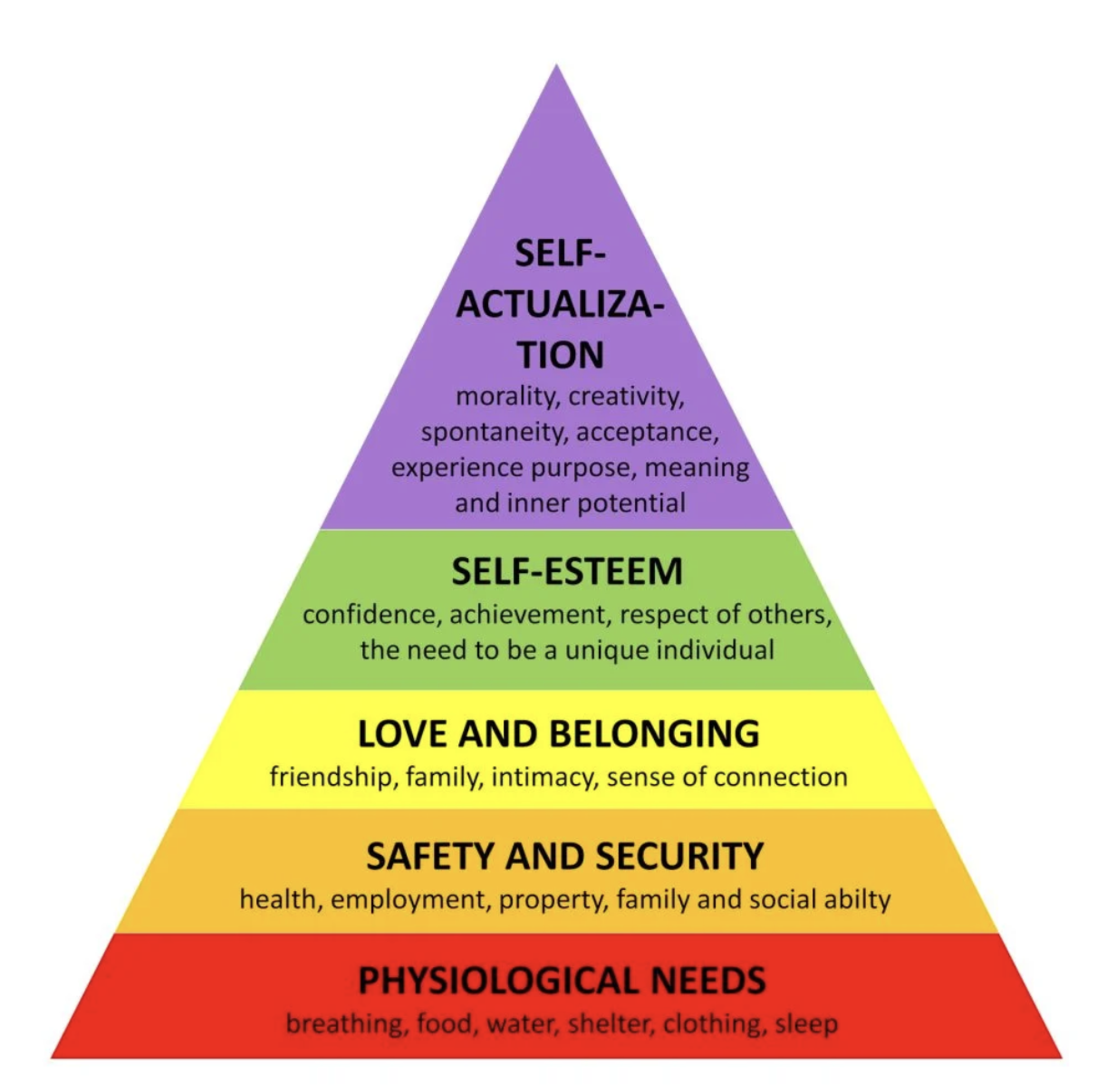

A sign of renewed health is that your behaviour re-aligns with what is expected, with what enables you to fit into ‘normal’ society. You’ll know you’re better because your productivity returns. You’re more functional. You’re achieving, you’re growing, you’re self actualising. You’re on your way to sitting right up there, at the top of the pyramid of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, with the other winners.

Do these goals sound familiar? Do these standards for what it means to be ‘better’ or ‘healthy’ ring any bells? I feel rather unsurprised that the white men still influential in psychology today were children of the Industrial Revolution and the late 19th century, early 20th century iteration of financial capitalism that we still live within today.

The authority of the diagram: Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs

Conformity and Productivity as Signs of ‘Mental Health’

Flip through the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the bible of pathology that grows fatter with every edition and that now problematises a goodly chunk of human experience. How does one tell the difference between everyday struggles and a clinically significant problem? It’s this criterion:

Must cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

One must meet this essential criterion for most formal diagnoses. In other words, you can be ticked off as having enough of the symptoms to qualify for the label, but you also need to be judged about how well you’re fitting into the expectations of your environment.

Who determines what optimal social, occupational, or other functioning is? What are the values of the people who decide these things?

Read between the lines, look at the powers behind the thrones, and you’ll realise that productivity is an implicit marker of health in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Conformity to WEIRD norms and mores is an implicit marker of health. If successful therapy is all about returning to ‘normal’ functioning, AI therapy is perfect for that. AI is ideally set up to be a tool for achieving social conformity and optimising for productivity.

I think about all the WEIRD values that lurk in our notions of psychological health or pathology, and how these same WEIRD priorities are encoded into the technology platforms we use, the AI that is near-ubiquitous now. Autonomy. Independence. Productivity. Conformity. Efficiency. Frictionlessness. Comfort. Knowledge. Discernment of The Right Answer. Ability to articulate, explain, justify, argue coherently. Success. Rationality. Logic. Control. The absence of suffering. A constant personal growth imperative, paralleling the continuous growth imperative of capitalism itself.

What is Reid Hoffman talking about when he says an AI therapist should be 'safer' and 'better' than a human therapist, just as an AV may be safer and better than a human driver? Safer in what way? Better in the sense of what, in service of what? To determine whether something is 'better,' you must ask what’s being aimed for.

We were so close to challenging and overturning the limiting ways that we’ve historically thought about ‘better.’ So close.

The Brief Window Where We Started to Get Therapy Right

As the 20th century progressed, we started thinking about therapy differently. Carl Rogers and other humanistic and existential thinkers championed the healing power of the therapeutic relationship. The women's, identity, and civil rights movements made us think and talk about power dynamics in all areas of society, including psychotherapy. More women began training to be psychologists and therapists, and they now constitute the majority of practitioners, even if they do not dominate in influential groups like the American Psychiatric Association board that produces the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. More people of colour began entering the field. We began seriously interrogating the paradigms behind our assumptions about psychological health.

My clinical psychology doctoral education in the US, in the 90s and 2000s, benefited from these shifts. We studied intercultural therapy approaches, examined lifespan development from different gender perspectives, and read about race and racism in America. We learned from the feminist therapy movement, which began in earnest in the 1970s. We did challenging, reflective work on our implicit biases, internalised racism, and for those of us who were white (the majority in my doctoral cohort), our race-dependent privilege. We took a critical perspective on the history of psychology and psychiatry, its uses and abuses.

The things that are not well encoded in today’s online algorithms were very much a part of my psychological education.

But paradigms shift, and what I view as progress is not linear. Since my masters and doctorate, forces have pushed us back towards the unhelpful, rigid, WEIRD visions that dictated therapeutic approaches in the first three quarters of the 20th century. For example:

‘Evidence-based practice’ sounds like a good thing, but it lends itself to the idea that if something cannot be objectively measured and delivered in a standardized, manualised (and now scalable) way, you shouldn’t be doing it, or it shouldn’t be funded. Evidence-based practice is demanded by insurance companies.

Contextual, relational, culturally aware approaches have been marginalised again.

Insurance coverage prioritises short-term, efficient, standardised, culturally approved treatments.

Neuroscientific approaches, which can hold considerable wisdom and promise, are deployed in ways that reduce and decontextualise our experience, and this is encouraged by the all-powerful (largely American) pharmaceutical industry, that stalwart of WEIRD values.

So, I now think of my training as a rather brief, halcyon window, where we were explicitly taught to think deeply about culture and power as infused in the working relationship between therapist and client. We learned that the personal is often political, that what is cast as individual suffering to be targeted by medical (or now technological) solutions is often patriarchy-induced pain, or capitalism-aggravated suffering.

I emerged from my training seeing many ‘symptoms’ not as failings or brokenness, but as understandable adaptations to societal challenges and depredations. And, I understood that being with rather than doing to another human is a huge part of what makes therapy helpful. The client and therapist are in it together. Both struggle, strive to understand, grow, and are imperfect.

A disclaimer. I fulfil all the WEIRD criteria, although I’m not a man, maleness not being formally captured in that designation. I worked hard, but the game was always rigged in my favour. I cannot escape these situational givens. I can only question their impact with curiosity, humility, and reflexivity.

I may be WEIRD, but I hope I have a more healing, healthy, inclusive sense of the heart and soul of true therapy.

What Does a Human Therapist Mean by ‘Therapy’?

There are literally hundreds of therapies, 500 or more distinct schools or modalities. If we go even more fine grained, there are as many therapies as there are therapists: each practitioner achieves their special blend, their distinctive approach. If we go yet further, every therapist/client dyad is unique. The late great therapist, my mentor Hans Cohn, said, The client you meet is the client that meets you. There is no client as such.

Yet, despite the panoply of techniques and approaches, something makes an exchange recognisable as being therapy, as achieving therapeutic outcomes. What is it?

Researchers such as Bruce Wampold, Michael Lambert, and Mark Hubble researched this question and surfaced a number of common factors – elements that are present no matter what type of therapy is happening. And the research seems to indicate that common factors, not specific approaches or techniques, account for a huge amount of therapeutic change. While estimates vary, common factors account for between 30-70% of variance in therapeutic outcomes.

The therapeutic alliance, the collaboration, the bond, the relationship, the trust: this accounts for 30-40% of the variance in therapeutic outcomes.

Client factors account for 30-40% of therapeutic outcomes. Client factors are what’s going on in the client’s life outside therapy: their internal and external resources; their epigenetics; their existential and situational givens; their social situation and supports; their overall life circumstances.

Expectancy and placebo effects account for approximately 15% of the variance, including the client’s hope; their belief in treatment; their expectation that they will improve.

And how much of the therapeutic outcome is down to the specific model/technique? Again, studies vary, but probably around 15%.

The precise estimates have their critics, but even those critics agree upon two things: first, that the therapeutic relationship is indisputably critical and second, that specific techniques alone account for far less than the therapy industry often implies.

In The Heart and Soul of Change, common-factors researcher Mark Hubble describes how the therapist's ability to hold hope for the client, at a time when the client is struggling to have it themselves, is incredibly important. I have felt that more times than I can count.

An AI cannot hope. Humans instinctively understand this, however human-seeming the AI might be. In our darkest hour, when we search for hope from the AI, we feel its hollowness in the fibre of our being.

Mistakes are the Point

Hoffman’s comparison to autonomous vehicles reveals how fundamentally he misunderstands what I understand therapy to be. With self-driving cars, he says, the goal is to eliminate accidents, to engineer them out entirely. Mistakes are failures. Dings or crashes must be optimised away.

In therapy, mistakes are not failures. Rather, they are central to the work.

I try to be aware of power dynamics with my clients, to work with them as my fellow travellers. I am far from perfect, and this imperfection is integral to therapy’s effectiveness. Like Winnicott’s good-enough mother, good-enough therapists encourage client growth. My imperfection, my messiness, my humanity are important things to model. The interaction is neither mechanistic nor glitch free, and nor need it be, for the friction drives the process.

Sometimes there will be ruptures between my client and me. They are meaningful. We stick with it, stay open, stay present, seek clarity and healing. This is the real work. Incidents of rupture and repair are how humans learn to trust, to tolerate imperfection in themselves and others, to stay in relationship when things get hard. I hope our therapeutic work helps my clients navigate their other human relationships differently.

A short list of things that do not matter for therapy, AI or otherwise, and which may actually stand in its way:

Efficiency. Scalability. Perfection. Comfort. 24/7 responsiveness. 24/7 availability. The absence of discomfort, pain, and mistakes.

What the People Building AI Therapy Want

The therapy and AI industries are merging, and with that merger, the WEIRD assumptions and biases underpinning each supercharge and reinforce one another. AI therapy systems are being built primarily by WEIRD people, with engineering rather than therapeutic mindsets, funded by venture capitalists who demand scale and profit.

Reid Hoffman is a case in point. White, American, Stanford and Oxford educated, upper middle class, co-founder of PayPal and LinkedIn, the latter being a platform that is constantly referenced by my professional clients who suffer from social-comparison anxieties and insecurities. If Instagram has the potential to amplify toxic social comparison in teens and young adults, LinkedIn has the same effect for adult professionals.

Hoffman is saying we shouldn’t limit AI therapy because we don’t want to withhold enormous benefits from the people that need it most.

I wonder which benefits he means.

If you are a therapy client, you are not a passive passenger or hapless pedestrian. A therapist is not a programmed driver, trained to get you to that destination via the shortest and most frictionless route. Therapy is not a vehicle expertly calibrated to get you where you need to go with a minimum of fuss.

Let's not buy into Hoffman’s vision of what constitutes therapy.

Therapy is being with another human in their pain and struggle. It is messiness, imperfection, rupture and repair. It is holding hope when the client cannot. It is trust and vulnerability, and the willingness to connect deeply.

So when the WEIRD tech founders and the surveillance and venture capitalists that power them tell us AI therapy will be ‘better’, ask: Better at what? Optimising for conformity? Making you more efficient? Making sure you are maximally productive in your functioning? Becoming a more fully paid-up participant in work and love and consumption? Eliminating discomfort for yourself and others?

Because if so, these are not true therapeutic goals. These are capitalist goals, the same WEIRD values that have distorted and shaped our understanding of what constitutes ‘mental health’ for over a century. Now we encode these values into new, powerful algorithms that target and monetise our pain. These algorithms simultaneously and powerfully shape our discourse and beliefs about therapy and therapeutic change, reversing gains we were in some ways only beginning to make. More than ever, yes, the personal is political, and it is economic.

If we want a useful discussion about AI therapy, we need to understand what true, meaningful therapy is, the kind of therapy that benefits human thriving, peace, and cooperation on this planet. That kind of therapy results, I think, in more psychological and behavioural flexibility, more openness, and more ability to connect with and act upon what matters to us.

Those who are building AI systems for therapy are not optimising for those things.

The thing that AI is best at matters the least in successful therapy. The thing that AI is worst at matters the most.

When Reid Hoffman says ‘better,’ he may mean ‘more perfect at achieving the outcomes WEIRD culture most prizes’.

I doubt these outcomes are the heart and soul of truly meaningful change.

Looking for a keynote speaker who examines the assumptions and consequences of AI therapy? Book Elaine here.

Elaine is available for keynotes, workshops, panel discussions, and leadership events in the UK, Europe, and beyond, speaking on AI ethics, digital wellbeing, and the psychology of technology. Her talks on AI companions, AI therapy, and the monetisation of loneliness challenge audiences to question who is building these systems, what values they encode, and what we risk when we accept technological solutions to fundamentally human needs.