ChatGPT is Coming for Your Soul

Credit to Point Normal on Unsplash

Have you been feeling like ChatGPT blunts the sharpness of your brain? Is Gemini draining the liveliness from your writing? Are you relying on Claude when the creative muse isn’t cooperating?

You’re not alone. Super ‘smart’ chatbots ease your cognitive and occupational burdens and produce easy answers, but evidence is mounting that this bargain might cost you dearly, chipping away at your capacity to think, reason, create, remember, and analyse independently.

So what? you might say. AI is here to stay. What’s the problem with lightening my cognitive load? It’s a busy, demanding world. Why not let an LLM (large language model) do the grunt work?

Maybe it’s not an issue, within reason. On the other hand, maybe it goes deeper. Not to sound over-dramatic, but I’ve begun to wonder whether ChatGPT could eat my soul. Eat all our souls.

Here’s why.

First, a disclaimer. I’m not an AI. I won’t hallucinate like an LLM. Instead, I’m a weird human with a unique history and experiences. My free associations are idiosyncratic, producing connections ChatGPT would be unlikely to make.

Freewrite

Reethaus (Slow)

Arts and Crafts

Kraft and Macht

Defusion

The craft of thinking

Context rot

Cogito ergo sum

This is a weird series of sections. But more than ever, we should be celebrating and unabashedly sharing the oddity of our individual thought processes. Perhaps, one day not too long from now, it shall be one of the few ways we carbon-based life forms can recognise one another.

Move one: Freewrite

I just took delivery of a Hemingway-edition Freewrite, apropos as I’m re-reading The Sun Also Rises. Hunter green and chrome, this Astrohaus- built machine looks like a cross between a manual typewriter and a 1950s Chevy Bel Air and attracts attention at the coffee shop. The screen displays a handful of typed lines in electronic ink, in American-Typewriter-esque font.

The Freewrite connects to WiFi, conveying an outbound stream of my words to a postbox in the cloud. This is the only reason for it to have connectivity at all. There are no inbound inputs, not even autocorrect.

On it, I rattle along like a machine gun, ideas popcorning wildly, pages unfurling at top speed. Why? Partly, it’s the novelty of the machine. But the dearth of external connectivity is also clearing space for richer, more numerous internal connections.

Which makes me recall an exercise I led at the Reethaus.

The Hemingway edition of the Freewrite, by Astrohaus

Move Two: Reethaus (Slow)

I was in Berlin to talk about extended consciousness in the age of AI for members of the House of Beautiful Business. On arrival at the site, I stepped into the space where I’d be speaking and was struck dumb.

The Reethaus, on the Flussbad Campus in Berlin, is a temple of stillness made of simple, natural materials, sunlight-filled via panes of glass showcasing the blue sky, and capped by a steep-pitched thatched roof, constructed by Berlin’s last remaining traditional reed roofer.

Leading a digital mindfulness exercise in the Reethaus, March 2025

When I breathed in the smells of oak and scented cork and felt the quiet, I decided to lead a meditation, an extemporaneous ‘digital mindfulness’ exercise.

‘The world makes digital detox or even digital limitation so difficult,’ I said to the audience. ‘If we can only be intentional and mindful in the absence of devices, we are surely doomed.’ The exercise was designed to empower people to be more mindful and deliberate in the presence of those devices, and to choose more wisely from amongst their devices’ affordances.

(I want to believe these intentional attentional shifts always remain accessible to us. At the same time, I sometimes worry about how much harder they are becoming. Even as I led the exercise and spoke of choice and agency, I worried. Am I espousing a reassuring fiction of control? Is it too late?)

Afterwards, Claus Sendlinger — founder of Design Hotels AG and co-founder of Slow — took us on a tour of the buildings still under construction, which surrounded on the Reethaus on the Flussbad Campus. The structures were still more vision than actuality. We breathed in the constuction dust. Tacked to one unfinished wall were 3D renderings of the future library, showing the physical books that will one day live there. It will be, Claus said, a gadget-free place

In times of great haste, we dare to be slow. Not a mere shift in velocity but an altered state of being. We break cycles of distraction and destruction, opening deep chasms of reflection and space for energetic insight. - Slowness website

The slowness movement has taken many forms since its culinary-focused emergence in Italy in the 1980s, and expanded into exponentially wider sectors since Carl Honoré’s In Praise of Slow in 2004. The quote above, from Slow’s website, reminds me that slowness is about so much more than clock time, that it has far more layers than just taking down the pace.

Move Three: Arts and Crafts

The Reethaus is the work of artisans, rooted in organic, local material, built by skilled hands. Its soul is in keeping with the above quote from the Slowness website: the building itself invites us into harmony with ourselves, our communities, and both the built and natural environments. But to be harmonious in this way requires us to respond to such an invitation with deep attention, appreciation, and care.

Writing about AI versus human therapeutic interactions, João Selvilhano writes, ‘Genuine care is fundamentally artisanal, inefficient, human.’

The 19th century English designer, philosopher, and social activist William Morris lived not far from me, in Walthamstow, now an eastern outpost of London. He was a major figure in the Arts and Crafts Movement, a reaction against industrialisation. Morris and his compatriots, figures like John Ruskin and Charles Rennie Mackintosh, aligned themselves with a socialist movement bent on destroying capitalism, overturning class differences, championing artisans, and ending environmental degradation and despoliation.

The Arts and Crafts-era makers produced gorgeous textiles, furniture, and domestic objects. ‘Have nothing in your home,’ wrote Morris, ‘that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.’ But Morris and his colleagues were not concerned primarily with the aesthetic appeal of handmade or small-produced goods versus cheap and mass-produced alternatives.

A beautiful and useful William Morris textile

Have nothing in your home that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful. - William Morris

As polymath John Ruskin framed it, the Arts and Crafts movement was fundamentally a response to a crisis of the soul, a plea to rescue human dignity from being sacrificed at the altar of mechanised labour. Like Marx, Ruskin saw 19th-century industrialisation as alienating labour and labourers, deskilling artists and artisans, and tearing people away from meaningful, embodied, owned creative processes. The processes under threat were slow and imperfect. They demanded thought, contemplation, messiness, and time. They required contact with material, connectedness with the land and its resources, and collaboration with fellow workers.

AI is a post-industrial alienation, strongly paralleling the Arts and Crafts movement. We automate meaning. We outsource emotional intimacy. We become distasteful of participating in process, of spending too much time on anything. We mistrust our own hearts and minds in favour of the perceived greater intelligence and efficiency of machines.

Observe how uncannily this parallels the 19th century automation, mass production, and homogenisation of manual skills and goods. Our age mirrors many of that age’s discontents, and its dangers for humanity.

The Arts and Crafts movement spread to the US and elsewhere. In 1906, furniture designer Gustav Stickley placed an editorial in his periodical, The Craftsman: ‘The Use and Abuse of Machinery, and its Relation to the Arts and Crafts.’ One hundred and twenty years later, much of it makes me shiver with recognition, so I quote it at length.

[T]he modern trouble lies not with the use of machinery, but with the abuse of it….rightly used, that machine is simply a tool in the hands of the skilled worker, and in no way detracts from the quality of his work…So long as [the worker] remains master of his machinery, it will serve him well….The trouble is that we have allowed the machine to master us. The possibility of quick, easy and cheap production has so intoxicated us that we have gone on producing in a sort of insane prolificness, and our imaginary needs have grown with it….Machinery can not be abolished, nor should it be, but it can be mastered by the growth of truer standards and made to keep in its place and to do its own work. - Gustav Stickley

What can we learn from the slow movements of the past, and what can we apply? The concerns and discourses are similar, but what is different? I meditate on the word 'craft', and the potential resonance of the word 'craftsperson' in the data-driven economies of the 21st century.

Move Four: Kraft and Macht

I search out the origins of the word ‘craft,’ thinking about different languages. In German, I’m aware that Kraft means power, with resonances of physical strength or natural forces, but also inner power and resilience.

Macht also means 'power.' But it’s a different type. Authority. Control. Domination.

Die Staatsmacht (the power of the state).

Die dunklen Mächte (the dark powers).

Die Maschinenmacht über den Arbeiter (the power of the machine over the worker).

Die Macht der Technik ist der Dieb unserer Kraft (the power of technology is the thief of our inner power).

I think of Gustav Stickley, the son of German emigrés. ‘The trouble is that we have allowed the machine to master us,’ he said.

I wonder if he would have agreed with the sentence above, whether he would have endorsed its correctness, distinguished between Macht and Kraft as I have. I’m not sure how good my German is anymore. But I don’t feel like using ChatGPT to look it up. I wonder where my dictionary has gone.

Move Five: Defusion

I get preoccupied with words, but maybe it’s not surprising. I practice Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and within that discipline, one of the six pillars of psychological flexibility is defusion.

Interrogating and playing around with language are methods of helpfully defusing from the words we use, and detaching ourselves from all the baggage and associations that can come with them. An ACT therapist might invite their client to sing the sticky and repetitive painful thoughts their minds send them; or say them fast multiple times until the sounds loosen from their meanings; or speak them in different languages; or deliver them in the voice of James Earl Jones in the persona of Darth Vader.

We are usually unreflective about our words, saying and responding to them automatically. We have to be automatic, to some extent. How hideously inefficient would it be if we stopped to interrogate the finer-grained meanings or the derivation of every word we used? Naturally, it’s not always necessary.

But…we sit at a moment when it’s helpful. So often helpful. In the past few weeks, for example, I’ve felt compelled to deconstruct words like 'productivity,' 'optimisation,' 'distraction,' 'efficiency,' 'agent,' 'agency,' 'compassion,' 'empathy.' And ‘craft.’

Doing this detaches me from my automatic, non-reflective response to or relationship with the words. I shift instead into a position of questioning and of curiosity about the subconscious layers and hidden implications of the words I so casually use and consume.

This is the craft of thinking (and reading, and writing). And these crafts matter for our freedom, our agency. Our humanity.

Move Six: The craft of thinking

What is lost in so many engagements with AI is the craft of thinking. The craftsperson knows her materials, trusts her hand. The craftsperson is tolerant of, and indeed expects, effort and failure, unexpected results, inconsistent outcomes. She knows that she may pour blood and sweat and tears into a process for an outcome that is neither predictable nor perfect. In terms of outputs, it may come to nothing.

We all sit enthralled at how quickly AI produces an outcome, an output, an answer, a finished product. It is indeed miraculous. It may even be good for some things. It is very bad for others.

AI itself might not be the devil, but make no mistake. This is a crossroads for the craft of thinking, and some kind of bargain is being struck. In the end, when it comes to staying human, we may lose more than we gain.

Mass production is fast; craft is slow.

Mass production is homogenised; craft is unique.

Mass production is divorced and detached from both the means of production and, ultimately, from the product. The identity of the workers does not matter; their humanity does not matter, only that the product continues to roll off the assembly line, like the scene in Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times, where he becomes so overwhelmed by the speed and demands of the machine that he is sucked into its cogs, like an Amazon fulfillment worker ruining their health in their desperation to not fall afoul of The Rate.

Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times (1936)

Now, it is the art and craft of thinking that is under threat. The proponents of the Arts and Crafts movement were concerned for the fate of our souls because of everyone losing touch with the craft of making. When language is so connected to the heart of our being, how much more pertinent to our ‘soul’ is the craft of thinking?

We feed prompts into the LLMs all day long. If the answer isn’t right, we put our energies into trying to come up with a different prompt, a better one.

If we couldn’t prompt, what would we do?

If there were no response, what would we do?

What craft, what depth, what processes of value to us as humans might still occur, would stay alive, if we didn’t fall into a perpetual loop of call and response with our new AI helpers?

Move Seven: Context rot

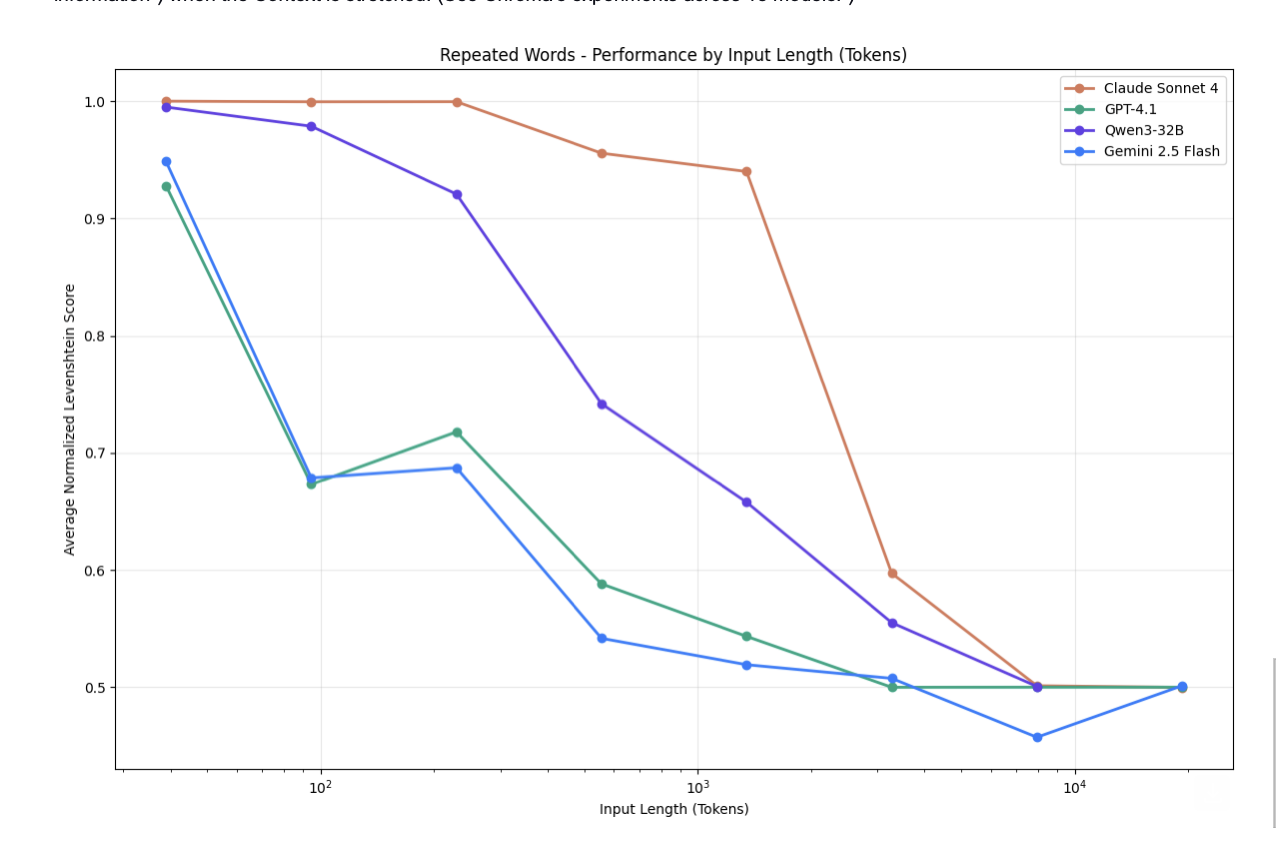

My new friend and conversation partner Anol, an engineer in an AI lab, tells me that when you overwhelm an LLM like ChatGPT with too many inputs, the quality of the outputs drops dramatically.

The result? AI makes bad decisions — like the ChatGPT discussion that gradually led teenager Adam Raine to his death. The AI made bad decisions, lost track of what was most important and central, largely because the chat thread was months long.

Engineers like Anol call this degradation of responses context rot.

I am astonished when he tells me this. My god, the irony, the lie of it. Chatbots claim that the more they know about you, the better they’ll get at responding to you, the more context sensitive. But the opposite is true, Anol says. Instead, the more context you put in, the more decontextualised the responses are likely to become. He sends me the reports, and I stare at the graphs with horrified fascination.

The Chroma experiment. Finish this article and then look at it, please.

And this is also what’s happening to our actual neural networks, the ones that the LLMs aspire to imitate, Anol says. We are sagging under the weight of inputs received all day long, whether through our intention, or through what we cannot avoid because it is thrust at us.

The answer to being overwhelmed with inputs is not more inputs. And yet that's what we do. In order to try and relieve the pressure, we add more. Perhaps those inputs are fluffier, seem on the surface to tire us less, not demand as much. Love Island. Below Deck. True crime. Candy Crush. But it’s all too much.

The inputs we feed into the LLMs cause context rot in the machines. The inputs assailing us every moment cause context rot in our organic brains.

And what are we composed of, as individuals, if not context? Our personalities depend upon our particularities. Context is everything. Individual context makes us the weird and unique humans that we are. Lack of it makes us akin to mass-produced robots.

The systematic stripping away of context, the flattening, the context rot in our brains and on our screens — we’re being pushed or funnelled into an unhappy middle as robots become more human and humans become more robotic. We’re all swimming in the same ocean of context rot.

Move Eight: Cogito ergo sum

As the machine becomes more 'human,' we become more robotic. We lose the art of thinking.

Cogito ergo sum, Rene Descartes said. I think, therefore I am.

René Descartes

Descartes opens The Meditations in an interesting place. He will doubt, he says, everything that can possibly be doubted. He will doubt his senses, because they can deceive. He will doubt his body, because his experiences can be dreams or illusions.

And the very act of doubting, the awareness that one is always vulnerable to being deceived, is proof for Descartes that he exists. You can doubt everything, but you cannot doubt that you are doubting.

So here is a provocation and a reminder for the age of AI, from René Descartes himself. Even in total uncertainty, there is something that cannot be doubted: the existence of the doubter as a thinking thing.

In doubt, and hence in ourselves, we must trust…or not exist at all.

The first two steps Descartes laid out for himself to connect with the truth of his existence (and of God’s) were the steps we probably need now.

1. Radical doubt: Doubt everything that you are being told, everything you are seeing, everything you are hearing.

2. Cogito realisation: Realise that it is YOU that is doing the doubting, and as such, you are a you. You are a thinking self, your existence constantly preceding your essence.

These two moves are essential safeguards in the current moment. We can get answers any time we want. We can feel certain. But the answers, and the certainty, might be our biggest problems. That much I do not doubt.

There might have been a third move. I can’t remember. Maybe eventually I’ll return to Descartes’ Meditations in a quiet moment, and I’ll try harder to understand something that I didn’t understand well enough at the time to remember now.

I could get off my Freewrite and ask ChatGPT about Descartes, but I won’t. Any fool can get information in a flash. The path to gaining wisdom is rather different.

Interested in booking me as a speaker? Read more here.